23-F: Gunfire in Spain's Parliament and Tanks On The Streets

On the 23rd of February 1981, gunfire erupted in the Congress of Deputies as a group of armed rebels attempted to do away with democracy and install a military government.

At 6.23pm on the 23rd of February 1981 - 40 years ago last week - the Spanish Congress of Deputies was in the process of electing a new prime minister. As the votes were being taken, Antonio Tejero, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Guardia Civil, strode in holding a gun. Climbing the steps to the dais, Tejero looked momentarily ridiculous, standing there alone with his big moustache and tricorn hat, and when he shouted ‘quieto todo el mundo!’ - everybody down! - the 350 members of the parliament merely looked bemused, as if they thought they were hallucinating. A moment later, a stream of far more serious-looking guards marched in carrying machine guns, which they soon let off in the direction of the chamber’s ornate ceiling, to the shock of everyone in the room, and almost everyone listening on the radio. Plaster and dust rained down on the politicians. At the sound of gunfire, they threw themselves under their chairs. All except three.

They were Manuel Gutiérrez Mellado, Santiago Carrillo, and Adolfo Suarez, and to the invading coupists, all three were traitors in different ways. Gutiérrez Mellado had a been an army man all his life; but in Tejero’s eyes he had betrayed the military. As defence minister, he had been tasked with reforming the powerful army, much of which was still loyal to Franco’s ideals. When Tejero and his men stormed in, Gutiérrez Mellado, nearly seventy years old, got up and began remonstrating with them, resulting in Tejero trying and failing to wrestle him to the ground.

Santiago Carrillo had been the leader of the Spanish Communist Party since 1960 - when it was an illegal organisation - and had fought for the republic during the civil war, before going into exile for years and then leading the party into congress when democracy returned. For Tejero he was a total traitor; not just to Spain but to Christian values. Carrillo stayed obstinately in his chair while his comrades cowered.

But the biggest traitor of all was Adolfo Suarez. Suarez had loyally served Franco before the dictator’s death, climbing the ranks and thriving. But with Franco dead, he became one of the fathers of Spanish democracy. As Spain’s prime minister during the transition, he destroyed the system which had put him in power. During his premiership he legalised Carrillo’s Communist Party and helped draw up the democratic constitution. After flinching from the gunfire, the prime minister stayed in his seat, telling those who asked why he didn’t get on the floor, ‘porque no me da la gana’ - I don’t feel like it.

Tejero hated democracy. In his eyes, and those of many other old Francoists, it was democracy which would rip Spain apart, democracy which would weaken the army, which would end in marxism, which gave hope to Catalan separatists and ETA’s terrorists who murdered policemen on the streets of the Basque Country. Democracy, only five years old, had to go. He wasn’t the only one who felt this way.

Before the assault on congress, Tejero had met with Lieutenant General Jaime Milans del Bosch and General Alfonso Armada. Milans del Bosch was in charge of the Third Military Region, which covered Valencia, Murcia and Cuenca. He was a committed monarchist. He had fought for the nationalists during the Siege of Toledo during the Civil War, and later in the Blue Division, which went to fight against the Soviets alongside Nazi Germany. Now he was old, near the end of his career, and living in a Spain he did not recognise.

Earlier that day, he had gathered his commanders and informed them that ‘a very important event’ was about to take place in Madrid. As Spaniards listened to Tejero taking over the Congress on the radio, Milans ordered tanks onto the streets of Valencia and declared a curfew. That evening the orange trees lining Valencia’s streets were jolted by passing columns of tanks and troop carriers. The roar of engines echoed across the city. Supporters of democracy feared the worst, and neighbours offered shelter to the children of left-wing politicians for fear someone would come to take them away. It was 6.30pm.

Alfonso Armada was a political opportunist. He came from an aristocratic family and had also joined the Blue Division as a young man, taking part in the Battle of Leningrad. Back in Spain, he became an instructor at a military school, where he met Prince Juan Carlos. They developed a friendship, and years later when Juan Carlos became king, Armada was given the job of general secretary of the royal household, which gave Armada political influence. He began to believe that he could become Spain’s prime minister. This hope was dashed, however, when he was removed from his post after using royal stationary to campaign for the right-wing Popular Alliance during the 1977 general election. In 1981, with Adolfo Suarez looking vulnerable and his rivals planning a vote of no confidence, Alfonso Armada began scheming once again. He would become head of a national unity government, and would use Tejero and Milans del Bosch to achieve this. He had told both of them that King Juan Carlos I supported the actions they were about to take. This was untrue.

Tejero had intended for the situation to only last an hour or so, ‘until the competent military authority arrives’. By this they meant someone like Armada or Milans del Bosch. But there was a problem. Tejero had believed Armada when he told him the king supported the actions. Juan Carlos made it clear early on that he didn’t.

At 7.47pm, the king called Milans del Bosch and demanded to know what was going on. Milans replied he had taken a series of measures to prevent disorder in the streets, and remained absolutely loyal to the king. In truth, he had ordered the tanks out in a show of force with the hope of convincing other generals to do the same across the country. Minutes later, the king’s secretary called Tejero in the Congress of Deputies to order him to stand down. Tejero replied that he would take orders from no-one else but Milans del Bosch, and hung up the phone. Spain was in for a long night.

Armada said later that he had known the coup would fail as soon as Tejero and his men let off their guns inside the Congress of Deputies. Such crass violence would be intolerable for many potential supporters of the coup. But Tejero didn’t know this, and he was kept in high spirits during the early part of the night by a man named Juan Garcia Carrés.

Carrés, a former leader of the fascist Organización Sindical Española - the national trade union which had been part of the Francoist system of government - had met with Tejero and Milans del Bosch previously. He had organised the buses which covertly transported the civil guards to the parliament building, drummed up positive press coverage and even promised Tejero that he would take care of his family in the event of Tejero’s death. During the occupation, he called Tejero to tell him the good news - the army was occupying the television station, and other military regions had joined the coup in support of Milans del Bosch. Although a group of soldiers had briefly taken control of RTVE, the second part of this was completely untrue.

By 11.50, the civil guards had been encamped in the Congress of Deputies with the 350 politicians for five hours. It was then that Armada arrived outside the parliament and asked to go inside to negotiate with Tejero. At the time, it wasn’t known how deeply involved Armada was in the affair, but the king and his associates had their suspicions, with one warning that Armada was ‘up to the eyebrows’ in it. Armada was allowed in to negotiate with Tejero. But he had little success. Would he revoke the constitution and do away with Spain’s autonomous communities? asked Tejero. He wouldn’t. Would he ban the Communist Party? Not that either. What about terrorism in the Basque Country? He would see, Armada replied.

Armada proposed a civil government led by him, involving politicians from the left and right, which he believed would be acceptable to the Spanish people, and proposed that he go and put it to the politicians there and then. Tejero was scandalised. ‘My general, I haven’t held up congress for this!’ he exclaimed, and Armada was ejected. He had failed again in his dream of heading the Spanish government, and when the depth of his involvement in planing the coup came to light, he would be sent to prison. Tejero sulked in the Congress, while the 350 middle-class politicians became increasingly fed up and bold in their complaints.

Meanwhile, a television crew was at La Zarzuela, the royal residence, filming an extraordinary television address from the king. It was broadcast just after one in the morning, and showed King Juan Carlos I dressed in the uniform of the commander-in-chief of the military. After detailing the orders he had given to the army generals to obey the law, he ended:

‘The Crown, symbol of the permanence and unity of the nation, will not tolerate, in any degree whatsoever, the actions or behaviour of anyone attempting, through use of force, to interrupt the democratic process of the Constitution, which the Spanish People approved by vote in referendum.’

After this was broadcast, the coup was broadly understood to have failed. Soon after, the king sent a message directly to Milans del Bosch, ordering him to withdraw his units immediately and warning him that if he continued he could provoke another civil war. It was another four hours until Milans complied fully with the order, all the while claiming to have acted with Spain’s best interests in mind.

Tejero was eventually convinced to leave at midday. Footage shows him saluting and shaking the hands of his officers. Before leaving, he had negotiated an agreement whereby the 200 civil guards who had entered the Congress under his orders wouldn’t face punishment. The politicians were also finally allowed out, and had tearful reunions with their families.

Tejero was immediately arrested and jailed. Despite the drama and spectacle of his actions, the coup had been an unmitigated failure. The vast majority of the army, police, civil guard and civil society had stayed on the side of the constitution. The plotters had misjudged how Juan Carlos I would react to the situation, and neglected to do anything to force him to support the plotters. He was left to his own devices to call round army generals all night, making sure he had their support; to receive calls from neighbouring heads of state who encouraged him to face down the rebels; and finally to make a powerful television address, confirming the coup’s failure.

In prison, Tejero developed a sudden interest in democracy, because he realised it could break him out of jail. If he could get elected to the Congress of Deputies - the same one that he had held hostage - he could get parliamentary immunity, allowing him to leave prison. Running under the slogan ‘Enter parliament with Tejero!’ (¡Entra con Tejero en el Parlamento!), the party won 1.8% of the vote and no seats.

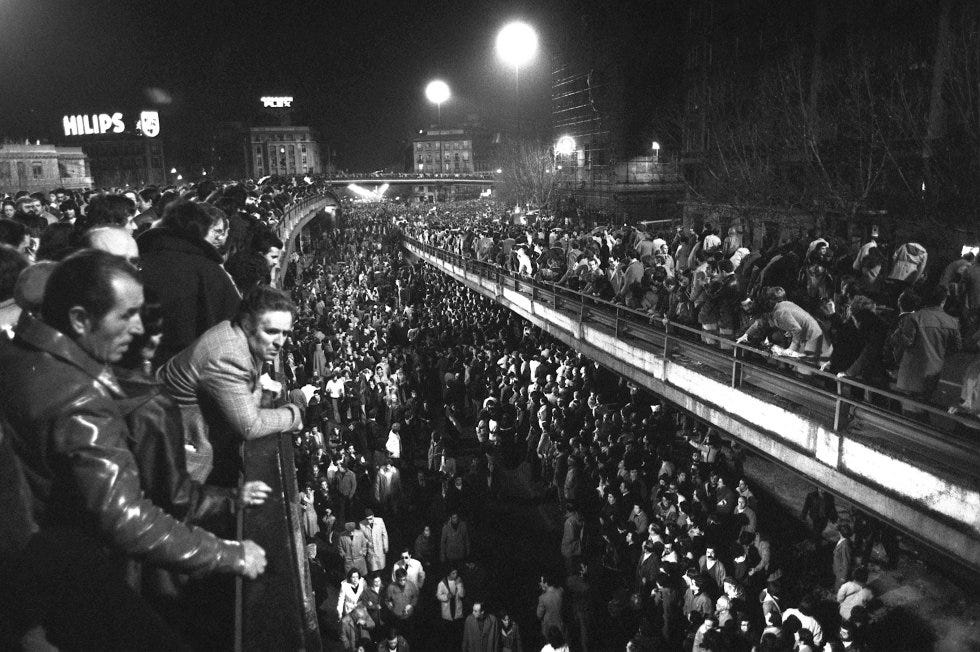

Many people today say that Spain’s transition to democracy was tepid, that it didn’t deal with the crimes of Francoism and left too much power in the hands of Spain’s aristocracy. But 23-F, as Spaniards call the coup attempt, is a reminder of how unstable Spain was at that time, and how young Spanish democracy still is. There were five other attempted coups between the death of Franco and 1981, though none reached the parliament. With the army and security forces full of powerful old men, suspicious of any project which would take power away from them, the path to democracy was a dangerous one. But because of the mistakes of the plotters and the determination of the majority of Spanish society, the trauma of 23-F solidified Spanish democracy. A week later, a million and a half people poured onto the streets of Madrid to protest in support of democracy, and one year later, they elected Spain’s first Socialist government.

Thanks for reading today! I love hearing from people with recommendations or requests for things I could write about, so feel free to reply to this email! You can also follow me on Twitter. If you enjoyed this email, and think someone else would too, hit the button below to share it.