The Island Which Changes Country Twice A Year

Every summer and winter for the last 361 years, France and Spain have been passing a small, unpopulated island back and forth between them.

The Bidasoa River flows north from Erratzu, in the Navarran Pyrenees, picking up the snowmelt from the mountains on the way. As it rushes down towards the sea through dark green hills, it becomes the border between France and the Basque Country in Spain. Because both countries are now part of the Schengen Area, many parts of the French-Spanish border are barely noticeable today, marked only occasionally by an obelisk on a hill or a disused and decaying customs post by the side of an old road. But this border was once one of the most heavily defended in Europe.

Within living memory, this border was fortified by the dictator Franco with sentries every hundred metres along the river to stop outsiders getting into Spain, and internal enemies getting out. Separatist terror group ETA used the mountains to hide out, slipping across the border under cover of darkness.

Further back in time, in the 17th century, France and Spain were at war, in a conflict which had come out of the wider Thirty Years War between most of Western Europe. It had been a bloody, pointless and tiring affair mostly fuelled by over-ambitious royals jostling for power. After 24 years of bloodshed, with numerous atrocities inflicted on civilians and the countryside ruined by constant warfare, both sides agreed to negotiate an end. The result was the Treaty of the Pyrenees.

The treaty slightly redrew the border between the two countries, giving some counties in the northern part of Catalonia to France. It also specified that all villages north of the Pyrenees would pass into French hands. This resulted in the creation of a Spanish exclave, Llívia, because it was considered a town. Llívia continues today to be a Catalan municipality completely surrounded by France. There was some minor reorganisation at the Basque end of the border too, changing the course of history forever for a few insignificant villages.

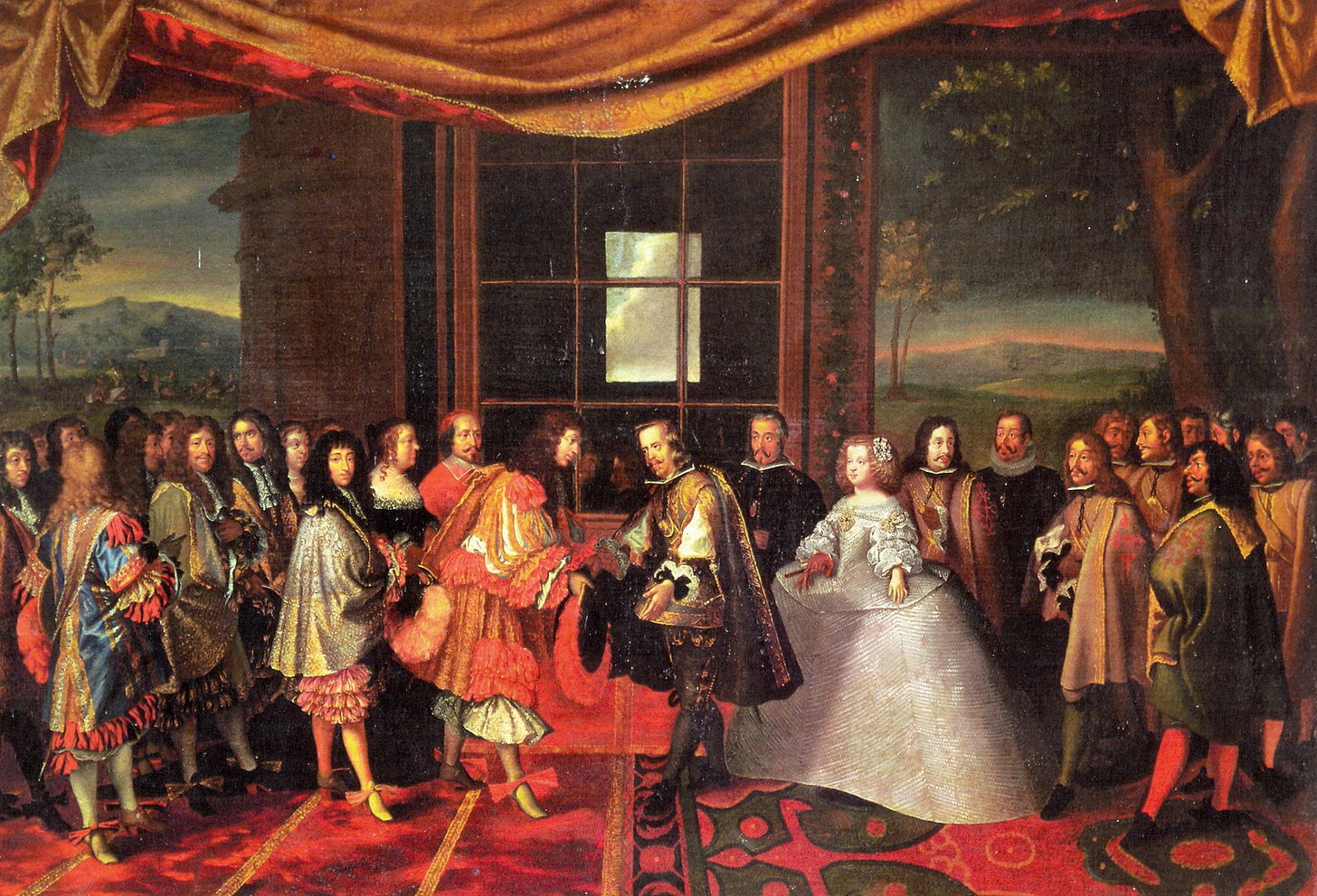

Another stipulation was that King Phillip IV of Spain’s daughter Maria Theresa would be married to Louis XIV of France. European royals in the 17th century behaved much like American socialite families do now; intermarrying in order to increase their power and wealth. From the French point of view, the marriage would mean any child between the couple would become heir to the Spanish throne, meaning a union of the crowns which would make Spain subservient to France. The Spanish understood this and negotiated hard to avoid it. Maria Theresa was stripped of her succession rights, but only on the condition that the Spanish paid a large dowry to France. Spain, impoverished and bankrupt, never paid it. This led to another war eight years later.

The egoistic kings of Spain and France needed neutral land on which to sign the treaty. Someone had the idea of conducting the ceremony on Pheasant Island - Isla de las Faisanes in Spanish, Île des Faisans in French, Konpantzia in Basque - a small, unpopulated island in the middle of the Bidasoa, between the settlements of Irun, on the Spanish side, and Hendaye, on the French, which had never been officially claimed by either side.

Naturally, this raised the question of to whom the island should belong. A clause was inserted into the treaty declaring that the island would be shared between France and Spain. But this wouldn't mean they would co-operate in governing the island together as friends. Instead, for six months of the year, the island would be French, and for the other six, it would be Spanish.

In 1659, the monarchs, flanked by soldiers, met on the island and signed the treaty. Maria Theresa, who didn’t have much say in the matter, was handed over to the French king by her father. Peace had been achieved, at least for a few years.

The island’s situation endures today. The island is still unpopulated, with visits prohibited, and the only reminder of its history is a rain-damaged stone monolith commemorating the events which took place there over 350 years ago. From the the 1st of February until the 31st of July the island is Spanish, and from the 1st of August until the 31st of January it is French. The countries’ respective naval commanders used to hold a ceremony twice a year on the island to hand it over - nowadays it changes hands without any spectacle. Depending on the time of year, the parks authorities of either France or Spain enter the island in order to carry out maintenance, and occasionally the local police force is given cause to chase young campers off it. It’s a situation which means the total size of the two countries changes twice a year by 0.0068km2.

Young people in Irun and Hendaye know little of the island’s strange story. Visually, everything about it belies its historical significance. It is a small island in the middle of a river - 200m long and 40m wide - and every year it gets smaller, as the melted snow from the Pyrenees becomes fast-moving water and gradually erodes the island. Though they’re both happy to cut the grass and prune the trees, neither of these once great nations are willing to spend money to stop it. Eventually, Pheasant Island will be eroded into non-existence, much like the empires over which the 17th-century kings of France and Spain once fought.

Thanks for reading today! I love hearing from people with recommendations or requests for things I could write about, so feel free to reply to this email! You can also follow me on Twitter. If you enjoyed this email, and think someone else would too, hit the button below to share it.