The Valencian Monastery Where Time Stands Still

Secluded within a valley in the Serra Calderona, stands a monastery with a 700-year history, whose monks are experts at self-isolation.

Back in late March as Spanish society was turned upside down by the pandemic and we were all adjusting to being locked in our homes; the shutters pulled down on our favourite bars and not a sound to be heard on once-bustling streets, a spokesperson stated that in the Cartuja de Porta Coeli - a 700-year-old monastery in the hills outside Valencia - nothing had changed at all.

‘Nothing has changed, the life of the monks is the same, they are still in their cells, they are always confined,’ said the person who attended the telephone - a functionary employed by the monks to handle administrative tasks. The monks in Porta Coeli - ‘heaven’s door’ in Valencian - live in strict isolation, as part of the Order of Carthusians, founded in 1084. The Carthusians are one of the strictest orders. The monks live alone and pray alone, only allowed to socialise with each other on Sundays and other special days. They don’t engage with the outside world unless they have to. The last time this happened was in 1994, when a nearby forest fire threatened the monastery. Then, the monks moved out to a nearby town for the night.

I found the Cartuja (Charter house) by chance. It was a Sunday afternoon two years ago and I had spent it whizzing around the Serra Calderona natural park on a rented motorcycle with a friend. A particularly pretty road took us on a route partly carved through rock. When the walls of rock disappeared, the sunbaked, evergreen Valencian countryside sprawled before us with no human presence in sight. Then, from behind a hill, there appeared unannounced a bell tower, followed by a series of slanting terracotta roofs and sand-coloured stone masonry surrounded by well-trimmed evergreens and the occasional palm tree. It was like a mirage in a desert. The dignified cluster of buildings grew larger before disappearing behind trees. Moments later we were at the big wooden gate of the monastery.

When I turned the engine off we found ourselves bathed in the golden silence of the Serra Calderona. The monastery was surrounded by high hills on three sides, and the road back to the city was a long one. The only sound was the sighing of the wind as it shook the bushes and trees. ‘No visitors,’ read a sign next to the gate. ‘Respect the solitude of the charter house.’ One could imagine how there, isolated in the middle of all that silent splendour, it would be easy for a devout believer to feel the presence of God.

When we went back down the road, we passed a small group of monks taking their Sunday exercise. Four of five male figures wrapped in austere, flowing white robes, some of them old enough to require the use of a cane to walk. They waved us a cordial hello, and continued on their way home, where they would continue to live as if the 13th century had never ended.

We continued back to the city, where I would later find out that barely anyone knows much about the monastery - even people who grew up here. When I said its name and described it, I would normally be met with blank stares.

Construction began in 1272, in the newly-conquered lands of Valencia, which Jaume I had taken from the Moors in 1238. Since then, the Cartuja de Porta Coeli has seen the whole of Spanish history and barely been weathered by it. Time seems to move slower. During the Civil War, while Valencia was the capital of Spain and Madrid was under siege by the nationalists, the President of the Republic, Manuel Azaña, stayed in La Pobleta - an estate on the lands of the monastery. As the forces of fascism moved ever closer, Azaña wrote in his diary about his surroundings: “In this countryside, absolute silence, Mediterranean sun, the smell of flowers. It seems like nothing is happening in the world.”

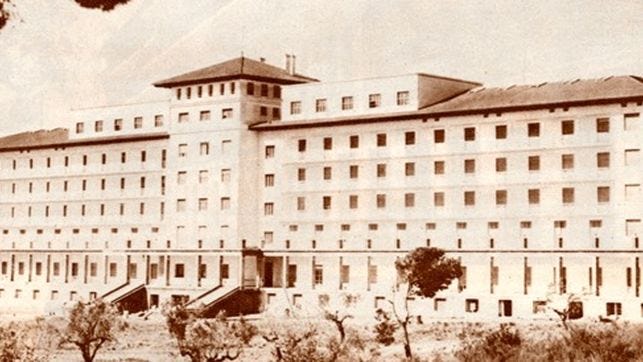

Three years later, during the dark early days of Franco’s dictatorship, part of that same land was used as a concentration camp for republican soldiers and sympathisers. About 4,400 former fighters ended up there, arriving by train, 100 of them to a wagon. An estimated 2,238 people were shot there between 1939 and 1956 - their deaths recorded as being from tuberculosis. On this site there now stands a hospital - Hospital Doctor Moliner. The building housing the hospital is the same as that which housed Franco’s prisoners.

The Cartuja, whose ownership had been taken over by the state when the republic was formed, was given back to the monks by Franco in 1946. A local regiment of the army helped restore the monastery, construct a reservoir and dig wells. Today, the complex now boasts a refectory, a chapel, a library, a cellar, stables, a smithy and a multitude of religious paintings - all kept well away from the public eye.

For a time, until three years ago, the monks held public masses on Sundays which would be attended by a few locals, and would occasionally permit visits by the public. But this has now stopped - the reason given being that people would sneak into the cloisters and take the monks by surprise, disturbing the solitude and quiet. So the monastery is completely closed once again, off-limits to anyone but the monks and their small staff of administrative and farm workers, who take care of the vast orange groves surrounding the complex. This has generated friction between the monastery and Valencia’s local government, with the government reminding the monks that the monastery is now considered part of Spain’s heritage and therefore must be accessible to the public and government auditors, who want to keep an eye on the ancient building’s structural integrity.

The monks, despite the lack of mobile phones in the monastery, know about the pandemic. Their isolation from the public has allowed them to avoid any outbreaks, which considering the advanced age of many of the monks would be calamitous. The prior meets the monks weekly to inform them of matters concerning the outside world which are considered ‘transcendent’. After such meetings, the monks walk serenely back to their rooms and continue a voluntary confinement which will last a lifetime, secluded in Valencia’s serene, silent countryside, far away from any earthly worries.

Thanks for reading today! I love hearing from people with recommendations or requests for things I could write about, so feel free to reply to this email! You can also follow me on Twitter. If you enjoyed this email, and think someone else would too, hit the button below to share it.