Welcome To Weird Spain

Spain is different, goes the saying. Odd stories, strange places, interesting news reports and their historical backgrounds.

Note: You’re receiving this because you subscribed to my other newsletter, the one which most recently told you about that time Scotland tried to colonise an inhospitable part of Central America. I’ve decided to launch a new one focusing on Spain. If you enjoy my other newsletter then I’d encourage you to remain signed-up to this one, because it will be broadly the same style, the only difference being that it’s related to Spain. If you’d rather not receive it, you can cancel your subscription here.

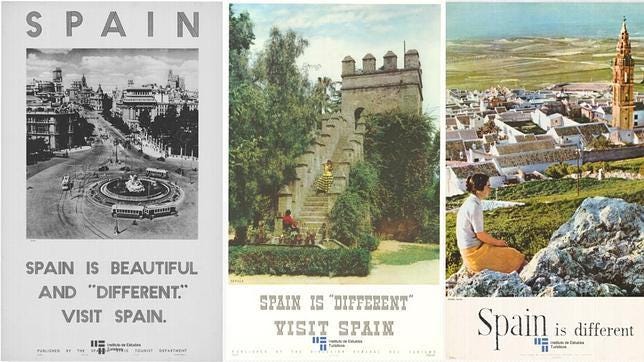

Spain is different. This slogan, invented by dictator Francisco Franco’s tourism minister Manuel Fraga in the 1960s, drew dark laughter from Spaniards. Spain certainly was different - it was one of only two states in western Europe to still be ruled by a right-wing dictator - the other being Portugal. Today, the phrase is still in use by Spaniards, often without knowing it was invented by one of Franco’s associates. People say it wryly, momentarily switching to accented English at the end of a diatribe in rapid Spanish, to make light of some annoying bureaucratic requirement, antiquated custom, or perceived problem in the country. ‘Bueno pues, Spain is different, no?’ Only the other day a friend of mine used it while talking about how Spain has handled COVID-19.

But Spain is different. Sure, every country is different, but Spain perhaps more so due to its long and tangled history, about which so many people here are still, consciously or unconsciously, involved in a tug of war.

Among Spanish history lie a million lesser-known stories. Stories of Gypsies and Sephardic Jews, of the Basques, of Catalonia’s once nascent and now surging nationalism, of art and literature, of corruption, of social experiments, of coup d’etats, revolutions, and terrorist attacks.

Since Franco’s death in 1975, Western Europe’s newest democracy has developed at a feverish pace, its people doing their best to look forward to a brighter future rather than back on a dark past. But no matter how hard they try, the past is present.

It’s present in the passion and sense of grievance with which Catalonia’s separatists argue for their independence; in the hostile welcome the Basque EH Bildu party receives in Spain’s parliament; in Emeritus King Juan Carlos’s sudden abandoning of his country, and in the fanatic levels of hatred people on Spain’s right-wing reserve for the leftist Deputy Prime Minister Pablo Iglesias. It’s present outside politics too, in Spain’s architecture, cuisine, and regional festivals. It’s present at the side of the road - in the motorway sex hotels, in the derelict nightclubs dotted around Valencia, in the empty, lonely villages of Castilla y León, in hilltop fortresses, in the Camino de Santiago, in the ‘expat’ urbanizaciones on the Mediterranean coast, as well as under the earth, where the bones of many civil war victims still lie in unmarked graves.

Spanish newspapers, written for Spanish eyes, don’t contextualise the stories they report. This means immigrant readers like me actually only see half the story. The other half is to be found in that activity that many Spanish people are uncomfortable with: looking to this country’s fascinating past, and investigating why the culture is how it is. This is what I intend to do in Weird Spain. While Spain’s news outlets report the ‘what’, I want to find the ‘why’. I want to understand - and help you understand - this country. This might mean unpicking a recent news article, or it might mean deep-diving into a story from history. It also means sharing other good sources of information, as well as off-the-beaten-track places to visit. There may also be an occasional piece of practical advice for foreigners living in Spain.

Weird Spain is a newsletter for immigrants who want a deeper knowledge of their adopted home and its people, and hispanistas across the world who want to know more about what’s going on here, and why.